Archaeological Excavations at the St. George Tucker Garden: Interim Report

Graphics by

Christina Adinolfi

November 1994

Re-issued February 2005

| Page | |

| List of Figures | ii |

| Acknowledgments | iii |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Research Design | 2 |

| Site History | 3 |

| The Garden | 4 |

| Field Methods | 7 |

| Results | 9 |

| 6 × 6 Meter Unit | 9 |

| 4 × 2 Meter Unit | 14 |

| Future Recommendations | 18 |

| References Cited | 20 |

| Appendix I: Pollen and Phytolith Samples Recovered from the St. George Tucker Garden | 21 |

| Page | |

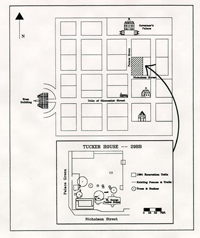

| Figure 1. Location of site shown on circa 1800 "College" map, and location of excavation units in relation to existing buildings and other structures | 1 |

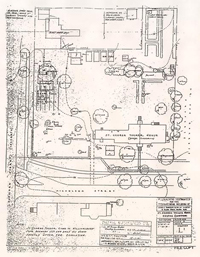

| Figure 2. Shurcliff's survey of existing conditions, circa 1928 | 5 |

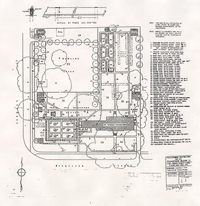

| Figure 3. Shurcliff's proposed site development plan, showing "as-built" conditions | 6 |

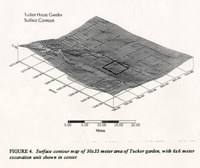

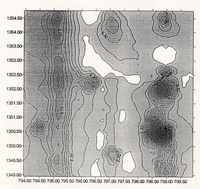

| Figure 4. Surface contour map of 30 × 35 meter area of Tucker garden, with 6 × 6 meter unit excavation unit | 7 |

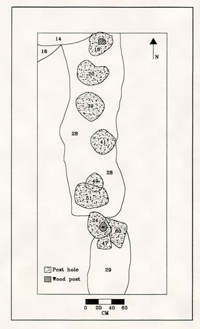

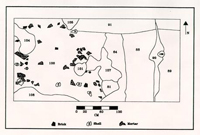

| Figure 5. Ditches and postholes along property boundary | 10 |

| Figure 6. Surface contour map in area of 6 × 6 meter unit, showing path and ditch/fence line | 11 |

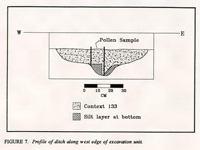

| Figure 7. Profile of ditch along west edge of excavation unit | 12 |

| Figure 8. Path features in 4 × 2 meter excavation unit | 15 |

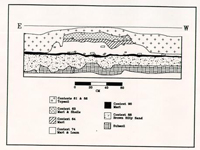

| Figure 9. Debris spread and central path in 4 × 2 meter excavation unit | 16 |

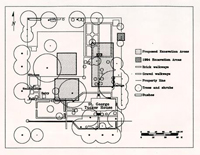

| Figure 10. Proposed excavation area—St. George Tucker garden | 18 |

Acknowledgments

Many people contributed time and valuable advice to the Tucker Garden Project. Project director Steve Mrozowski provided the research focus and was responsible for all aspects of the work. Paleoenvironmentalist Gerald Kelso extracted and analyzed an important set of pollen samples. We also wish to thank Kent Brinkley, Landscape Architect for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, for generously sharing his research and insight, and Terry Yemm of Landscape Services, for fruitful discussions and for taking care of things logistical. Other thanks are due to our colleagues in the Department of Archaeological Research, particularly Greg Brown and Andrew Edwards, who helped at every stage of the project. David Muraca surveyed the site both pre- and post excavation, while Meredith Poole provided advice and John Metz photographed the site.

Introduction

The St George Tucker house is located on Block 29 in Williamsburg's Historic Area, at the corner of Nicholson and what is now known as Palace Street (Figure 1). The lots (colonial lot numbers 163, 164, and 169) and the original 40 by 18½ foot house were purchased by St. George Tucker in 1788 shortly after his arrival in Williamsburg from Bermuda. The property is made up of three colonial lots and extant structures, including the eighteenth-century Tucker house and restored kitchen, three reconstructed outbuildings, and a twentieth-century garage.

St. George Tucker practiced law in Williamsburg and was one of the prominent eighteenth-century Williamsburg gardeners, maintaining a garden on this property for almost thirty years. Between Tucker's death in 1827 and 1992, the house was occupied by his descendants. While there have been some revisions to property boundaries since 1788, the bulk of the property has remained intact and largely unaltered.

Work completed by the Department of Archaeological Research during the 1994 field season represents the first intensive archaeological investigations to be undertaken on this property. Excavations took place over a ten-week period during the summer, performed by students enrolled in a field school sponsored jointly by the College of William and Mary and by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, under the direction of Marley R. Brown III, director of Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research, and visiting senior research fellow Stephen A. Mrozowski of the University of Massachusetts-Boston.

FIGURE 1. Location of site shown on the circa 1800 "College" map and (below) location of excavation units in relation to existing buildings and other structures.

FIGURE 1. Location of site shown on the circa 1800 "College" map and (below) location of excavation units in relation to existing buildings and other structures.

Research Design

Over the past sixty years the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has restored several gardens within the Historic Area, designed in the colonial revival style popular in the 1930s. Little attention was paid, however, to using emerging techniques in "landscape archaeology" to help in better restoring the eighteenth-century gardens to their original appearance.

In the past there has been little opportunity to archaeologically investigate gardens in Colonial Williamsburg. To date only the planting beds at the Peyton Randolph House (Edwards et al. 1988) and the gardens at Shields Tavern (Brown et al. 1990) have been studied in any detail. Gardens have been reconstructed based on documentary evidence or according to the ideals of the colonial revival style largely as interpreted by then-Foundation Architect Arthur A. Shurcliff in the 1930s.

The St. George Tucker garden represents an excellent opportunity to develop an in-depth research strategy for the study of gardens, since the property is largely undisturbed, Tucker was one of the most prominent Williamsburg gardeners in the late eighteenth century, and he left behind a fair amount of documentary evidence.

The immediate goal of these preliminary excavations was to begin to locate and define the plan of Tucker's eighteenth-century garden, as well as the later reconstructed colonial revival garden. In the short term this would allow Colonial Williamsburg to accurately restore the garden as part of its plans to develop the site. The long-term scheme, based on a multi-disciplinary approach involving future excavations as well as in-depth study of pollen, phytoliths, seeds, and artifacts, would allow us to investigate a well-documented garden, thereby providing insight into eighteenth-century gardening in the region.

Site History

St. George Tucker arrived in Williamsburg in 1771 to study law under George Wythe at the College of William and Mary. From a well-known Bermudian family, Tucker settled permanently in Williamsburg in the late 1780s after he succeeded Wythe as professor of law. When Tucker purchased lots 163, 164 and 169 from Edmund Randolph in 1788, the area was largely undeveloped. It contained three structures along west side of the property: Dr Gilmer's apothecary shop on the corner of Palace and Nicholson Streets, and a kitchen and house belonging to William Levingston (Dearstyne 1952:4). Until this time there was little or no development on the east half of the property, and early maps do not show any buildings located in that area. Shortly after purchase St. George Tucker moved the 40 by 18½ foot Levingston house, then facing Palace Green, to front on Market Square, changing the orientation of the lot. Through documentary evidence we know that over a period of time between 1789 and 1796 he renovated and enlarged the house, adding a kitchen, two wings and a "half shed extension" (Dearstyne 1952:13) in order to accommodate his large family. During this time several outbuildings also were constructed, including a dairy, a smokehouse, a well head, and a stable.

Tucker's correspondence, his poetry, and other papers give us considerable insight into the garden. For example, we know that he maintained both a formal garden and a kitchen garden and an orchard, likely enclosed by wooden fencing, throughout the thirty years of his occupancy (Martin 1992; Meatyard, personal communication, 1994).

In addition to his renown as a jurist St. George Tucker was a noted gardener in Williamsburg. While there is abundant documentary evidence about the garden, little is known about the plan. This period was one of transition and innovation in garden history, and Tucker may have designed his garden in any one of a number of different styles.

Following Tucker's death in 1827 the house passed into the hands of his wife Leila Skipwith Tucker, who occupied it in turn until her death ten years later. Since then Tucker's descendants occupied the house continuously until 1992, when it was acquired by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation upon the death of Dr. Janet Kimbrough, a descendent of Tucker and last life tenant.

The Garden

In the 1930s the house was restored by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. At that time, a garden was constructed by Arthur Shurcliff, the noted landscape architect then with the Foundation. Shurcliff, a disciple of Frederick Law Olmstead Sr., designed a "colonial revival-style garden north of the house, a boxwood and bulb garden located west of the house, and a large bowling green sited northwest of the house" (Brinkley and Chappell 1993:6). It was also around this time that the property line was moved east (to its present location) and that the boxwood hedge along that boundary and the box garden in the southwest corner were planted.

Before construction, Shurcliff surveyed the Tucker property in 1928 in order to document existing conditions. This plan (Figure 2) shows that there were a number of bushes, beds, and paths still visible. A second map, dated 1932, shows Shurcliffs "as—built" conditions (Figure 3). But apart from restoration work completed on the house in 1930-1931 and the construction of the garden about 1932, the maintenance and upkeep of the house and property has since been the responsibility of the tenants. Brinkley and Chappell (1993) note that by the 1960s little or no maintenance work was taking place in the garden.

Remnants of the 1930s garden are still visible today, although much of it has suffered from decades of neglect. None of the garden paths are extant, although the ground is very uneven and several of the paths are visible on the surface as low ridges. Evidence of a path also can be seen in the corn patch at the rear of the lot where there is a distinct lack of growth over one of these ridges. Brinkley (personal communication, 1994) noted that during the extremely dry summer in 1993 several additional paths and beds could be seen. Today only the central bed, which is badly overgrown and some plantings of Shurcliff are extant.

Previous archaeological excavations on the Tucker property have been limited to cross-trenching around the foundations of the restored kitchen and in the southwest corner of the property and to excavations around the Levingston house and near the reconstructed Play Booth theater. Shurcliff was reputed to have followed closely the footprint and contours of Tucker's garden during the construction of the twentieth-century garden. However, since no previous work has been undertaken on the property and since supporting documents are unclear, we are unsure how faithful Shurcliff was to the eighteenth-century plan, as he could see it, as well as how much he could actually see. As noted above excavation was halted at the level of the debris spread. However, the profile along the west wall indicates that the underlying stratigraphy is similar to that in the adjacent unit. Beneath the debris spread there appears to be a layer of dark brown loam underlain by the brown silty sand noted as context 29BB-88.

The excavations completed to date in this area suggest that there was heavy activity here throughout the Tucker and Coleman occupations. Not only is there clear, well-preserved evidence of Arthur Shurcliffs colonial revival path(s), but also of an earlier Tucker-period path. The disturbance over the 4 × 2 meter unit was minimal, so that both the early

5

FIGURE 2. Shurcliff's survey of existing conditions, circa 1928 (from Brinkley and Chappell, 1993).

eighteenth-century features and the later nineteenth- and perhaps twentieth-century alterations were also preserved.

FIGURE 2. Shurcliff's survey of existing conditions, circa 1928 (from Brinkley and Chappell, 1993).

eighteenth-century features and the later nineteenth- and perhaps twentieth-century alterations were also preserved.

The three upper paths have been identified as Shurcliff or post-Shurcliff paths. There is a similarity both in composition and in size that suggests that they are related to one

6

FIGURE 3. Shurcliff's proposed site development plan, showing "as-built" conditions (from Brinkley and Chappell, 1993).

another. Unlike the lowest path, which is flat, these have all been built up, crowned at the center. While the upper paths are made of marl, there is some evidence (as suggested by context 29BB-91) that there was also some brick rubble in the lowest path. The dates which were yielded from the artifacts show a progression back in time from 1880 for the uppermost path, to 1857 for the second path. The topsoil overlying these upper paths appears to be the result of a single episode. Furthermore, the three paths range from a minimum width of roughly 80 cm to 120 cm, while the lowest path is in excess of two meters. Finally, both the stratigraphic position of the lowest path and the nature of the artifacts within it suggest that it is an eighteenth-century feature.

FIGURE 3. Shurcliff's proposed site development plan, showing "as-built" conditions (from Brinkley and Chappell, 1993).

another. Unlike the lowest path, which is flat, these have all been built up, crowned at the center. While the upper paths are made of marl, there is some evidence (as suggested by context 29BB-91) that there was also some brick rubble in the lowest path. The dates which were yielded from the artifacts show a progression back in time from 1880 for the uppermost path, to 1857 for the second path. The topsoil overlying these upper paths appears to be the result of a single episode. Furthermore, the three paths range from a minimum width of roughly 80 cm to 120 cm, while the lowest path is in excess of two meters. Finally, both the stratigraphic position of the lowest path and the nature of the artifacts within it suggest that it is an eighteenth-century feature.

Field Methods

Prior to excavations a portion of the back yard area was surveyed using a Leitz "total station" combination laser theodolite/electronic distance measurer. Elevations were taken at 1 meter intervals over an area of 30 by 35 meters from the boxwood hedge in the east (the present- property line) to east of the central bed, and at 50 cm intervals within the 6 × 6 meter area finally chosen for the first excavation unit. Data was then plotted using Golden Software's surface modelling program, called Surfer. The resulting topographic map (Figure 4) shows two major ridges running north-south; a third, smaller ridge running along the boxwood hedges; and a raised area where the two main ridges appear to intersect. The area to the north of this intersection may be associated with earlier subsurface features although it is more likely that it is related to the small garden area located near there.

Two units were placed in the back garden of the Tucker House. The first—a 6 × 6 meter area—was located along the eighteenth-century property line, north of the garage. This unit was situated to the west of a twentieth-century utility trench and centered over a ridge which was visible on the surface. The second—a 2 × 2 meter square later expanded to 4 × 2 meters—was directly north of the back door in the area of the colonial revival central path.

The units were excavated stratigraphically by natural levels. The sod and upper topsoil layers were removed by shovel and screened through ¼" mesh. Layers below the topsoil were usually excavated by trowel and also screened through ¼" mesh. Pollen and phytolith samples were taken from significant features.

FIGURE 4. Surface contour map of 30 × 35-meter area of Tuckergarden, with 6 × 6 meter excavation unit shown in center.

FIGURE 4. Surface contour map of 30 × 35-meter area of Tuckergarden, with 6 × 6 meter excavation unit shown in center.

Each layer or feature (in Edward Harris' (1989) terminology a "unit of stratification") was assigned an individual "context" number and recorded in plan and, where appropriate, in profile. Context record sheets were filled out for each context, and all drawn maps were entered onto computer using AutoCAD drawing software. Field notes and other records are on file with the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Results

6 × 6 Meter Unit

The purpose for the 6 × 6 meter unit was twofold. First, it allowed us to work from known landscape features. In this case, this unit offered us the opportunity to investigate and identify the ridge visible on the surface. Secondly, by identifying the eighteenth-century property line it enabled us to locate the colonial boundary of the garden, thereby providing us with a known and definite Tucker-period boundary.

The 6 × 6 meter unit revealed a number of late eighteenth/early nineteenth-century landscaping features, some of which may relate to St. George Tucker's garden. Of particular note in this area are three features: the colonial fence/property line, a brick rubble path, and a ditch tentatively identified as a drainage ditch.

Underneath the sod was a series of uniform soils which range in color from dark brown to grayish brown (Munsell colors 10YR 4/3 to 10YR 5/2) and were usually classified as a clay loam. Up to three different topsoil layers were identified, each containing brick and some charcoal inclusions. In the deeper areas along the west side of the unit, there were up to two additional brown clay loams. Most of these soils were very similar both in color and texture, and were extremely difficult to distinguish one from another. Context numbers were assigned based upon differences in inclusions and/or the degree of mottling. The TPQs1 were mostly recent, and it appears that these contexts have been disturbed. TPQs range in date from 1845-1947 with no particular chronological pattern. Most of the features identified lay below these layers.

Among the few features identified within the topsoil strata, only context 29BB-11 was of note (other topsoil features were determined to be very recent and did not relate to either of the gardens). Context 29BB-11 was a semi-circular feature initially thought to be a planting bed. Upon excavation it became apparent that this was a very shallow feature, lying largely within the topsoil layers. Interestingly enough, this context yielded a TPQ of 1820, but its function is unclear. We do not believe that it relates to the eighteenth-century garden.

The three features of particular significance—the rubble path, the fence/property line and the drainage ditch—are each considered to be contemporaneous with the Tucker period and are likely associated with his garden. It is notable that all of these features run north-south and each lies equidistant from the other—that is, both the fence line and the drainage ditch are located approximately two meters east and west, respectively, of the rubble pathway. Whether this layout is deliberate and/or is related to the garden is difficult to determine without further work.

10The property line (Figure 5) consists of what appeared to be two linear ditch-like features, contexts 29BB-28 and 29BB-29, running north from the south wall of the 6 × 6 meter unit to a point just south of grid line 1353N, where they were truncated by a large rectangular feature (context 29BB-56). Contained within the ditches are nine post holes. Of the nine, two post holes had wooden posts intact within them and a third, adjacent to the north wall, cut into a later feature. Beneath these post holes a series of earlier posts were found. In total fifteen were found, nearly all of which yielded TPQs dating to the 1780s. Clearly this is a maintained property line with a set of colonial post holes and several replacement holes, some extending into recent history as indicated by the intact posts. Historical records indicate that the property line was in place from the eighteenth century until after at least 1932, when it was shifted to its present location, several meters to the east.

The ditch in which the posts sat was a deep straight sided feature with a flat bottom. At the surface it appeared that contexts 29BB-28 and 29BB-29 were two separate ditches, but they proved on excavation to be a single feature. At its deepest point the ditch measured 80 cm below subsoil. Few artifacts were recovered.

Running through the center of the unit was a line of crushed brick, oyster shell and mortar (29BB-43/44). The feature was narrow, measuring just over 30 cm at its widest point. At the south end of this feature there was a second, lower layer of a dark brown silty

FIGURE 5. Ditches and postholes along property boundary.

11

soil. The brown silty soil gradually tapered off towards the north, with the rubble at that end sitting directly upon the subsoil. It may be possible that the silty soil is related to the post hole which was found at the south end of the feature. This feature contained a large number of artifacts, including many wine bottle bases and finishes as well as large sherds of ceramics. Context 29BB-43/44 continues north to near the 1353N line where it is truncated by a later feature, picking up again just south of the north wall. Context 29BB-33 represents the north section of the brick feature where it reappears north of context 29BB-56. During excavation of the upper layers of topsoil between contexts 29BB-43 and 29BB-33 a high concentration of brick fragments, in a line, was encountered.

FIGURE 5. Ditches and postholes along property boundary.

11

soil. The brown silty soil gradually tapered off towards the north, with the rubble at that end sitting directly upon the subsoil. It may be possible that the silty soil is related to the post hole which was found at the south end of the feature. This feature contained a large number of artifacts, including many wine bottle bases and finishes as well as large sherds of ceramics. Context 29BB-43/44 continues north to near the 1353N line where it is truncated by a later feature, picking up again just south of the north wall. Context 29BB-33 represents the north section of the brick feature where it reappears north of context 29BB-56. During excavation of the upper layers of topsoil between contexts 29BB-43 and 29BB-33 a high concentration of brick fragments, in a line, was encountered.

The brick rubble feature has been tentatively identified as a path, and although it is narrow its position relative to the property line suggests that it could be a path bordering the east edge of the garden. When the brick fill was removed, it was clear that rather than the path cutting into the subsoil, it sat on top. At most the path was no more than a few centimeters deep. Furthermore, when the area was surveyed after excavation was completed, and a surface topographical map generated, it was clear that the middle section had been built up with the path at the crown and the ditch and fence line running along the sides of the ridge (Figure 6). The fact that the feature is built up is also evidence that this was a pathway.

Context 29BB-45 represented a post hole which lay beneath the rubble path. The post hole was dated to 1775 based upon a single piece of pearlware. No other posts were

FIGURE 6. Surface contour map in area of 6 × 6 meter unit, showing path and ditch/fence line.

12

found under the path nor did it appear to be associated with any of the other excavated features. Whether this represents an early or pre-Tucker feature, or whether it relates to an yet-unexcavated early garden fence or structure, is impossible to determine without further excavation.

FIGURE 6. Surface contour map in area of 6 × 6 meter unit, showing path and ditch/fence line.

12

found under the path nor did it appear to be associated with any of the other excavated features. Whether this represents an early or pre-Tucker feature, or whether it relates to an yet-unexcavated early garden fence or structure, is impossible to determine without further excavation.

The final eighteenth-century feature is a shallow ditch running north-south along the west edge of the excavation unit (29BB-133). The ditch that cut down into the subsoil was filled with a dark loam that is underlain by a layer of silt (Figure 7). A deeper channel ran through the rounded bottom of the ditch, and the channel itself was deeper at the north end, tapering off towards the south. This channel was filled with silt. Its purpose was unknown and has been tentatively identified as a planting bed or more probably a drainage ditch. Based upon artifacts found within, the ditch has been assigned a date of post-1820.

Two linear features overlay the north portion of the ditch, running south a distance of roughly two meters from the north wall. A yellow clay trench (context 29BB-97) and a darker brown linear feature (29BB-98) were found within the loam, lying above the subsoil. These features contained a number of late nineteenth-century artifacts. Both of these contexts were shallow with a depth of no more than four cm. Originally, these were thought to be a part of the drainage ditch/planting bed feature, but it was later determined that these two features were separate and more recent than the drainage ditch/ planting bed. We think that the ditch was undisturbed.

There appears to be only a single intact eighteenth-century layer, despite the several features which can be confidently assigned to the height of Tucker's gardening in the late eighteenth or the early nineteenth century. This layer (contexts 29BB-116, -117, and 121) consists of a brown loam. Contexts 29BB-116 and 29BB-117 ran down either side of the

FIGURE 7. Profile of ditch along west edge of excavation unit.

13

brick path feature and were not fully excavated. It appears that this layer might also have been present west of the drainage ditch, as context 29BB-121 was located in the southwest corner and lay above the subsoil. When excavated considerable slope downwards into the ditch was revealed. Pollen and phytolith samples were taken from the area and may assist in the identification of this layer. Within context 29BB-121 there was a small hole, context 29BB-134, which extended down into the subsoil. While its shape does not appear to be regular enough to be a post hole, it could represent a small planting hole. Again, phytolith and pollen samples were recovered from this feature. The TPQs from these layers all fall into the ubiquitous 1864-1880 range. However, these dates should not discount the possibility that these are eighteenth-century layers; rather, it is much more likely, since only the top of those layers was excavated, that many of the artifacts have been brought down from the upper layer. There has been considerable disturbance of the earlier features by twentieth-century alterations. Included among these is a large (tree) planting hole and other unidentified features, possibly related to the installation of the catch basin. As a result little if any of the early features remain east of 796E and north of 1353N.

FIGURE 7. Profile of ditch along west edge of excavation unit.

13

brick path feature and were not fully excavated. It appears that this layer might also have been present west of the drainage ditch, as context 29BB-121 was located in the southwest corner and lay above the subsoil. When excavated considerable slope downwards into the ditch was revealed. Pollen and phytolith samples were taken from the area and may assist in the identification of this layer. Within context 29BB-121 there was a small hole, context 29BB-134, which extended down into the subsoil. While its shape does not appear to be regular enough to be a post hole, it could represent a small planting hole. Again, phytolith and pollen samples were recovered from this feature. The TPQs from these layers all fall into the ubiquitous 1864-1880 range. However, these dates should not discount the possibility that these are eighteenth-century layers; rather, it is much more likely, since only the top of those layers was excavated, that many of the artifacts have been brought down from the upper layer. There has been considerable disturbance of the earlier features by twentieth-century alterations. Included among these is a large (tree) planting hole and other unidentified features, possibly related to the installation of the catch basin. As a result little if any of the early features remain east of 796E and north of 1353N.

The most prominent of the twentieth-century intrusions is a large rectangular feature (context 29BB-56) containing a circular clay feature (context 29BB-14). Context 29BB-14 was sectioned and the north half removed. Excavation revealed that it was filled with a number of smaller layers and lenses and was topped by a yellow-orange clay cap. The soil within context 29BB-14 was a very sticky hard packed clay, which necessitated its removal with a pick. Due to the recent date of this feature, which appears to be a tree planting or, more likely, removal hole, it was not completely excavated; once redeposited subsoil was encountered work was halted at a depth of 68 cm below the top of subsoil. Few artifacts were recovered.

For similar reasons the surrounding feature, context 29BB-56, was left unexcavated. But the excavation of the circular hole allowed a window into the side of 29BB-56, and thus we were able to determine that it was filled with mixed clays and contained at least two iron reinforcing bars.

It is thought that context 29BB-14 is a tree removal hole. Shurcliffs 1928 and 1932 plans (see Figures 2 and 3) show a line of trees running along the property line which were subsequently removed during the restoration. The function of the rectangular feature, context 29BB-56, is unknown although it may be possible that it relates to the removal as well.

The subsoil in the area is a light brown or tan clay and is typical of many of the sites within the Historic Area.

Clearly there has been considerable landscaping and/or alteration of the eastern portion of back yard during the latter nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Among the modern disturbances is the installation of the below-ground catch basin in 1936 or 1937 (Brinkley and Chappell 1993:7). Historical records indicate that drainage has always been a problem on the property and we may be seeing alterations due to this. There is no clear evidence of either Tucker-period beds or Shurcliff gardens in the 6 × 6 meter unit. The most likely reason is that this area either bordered on the garden or was outside its limits, and in either case was not used extensively throughout the occupancy of the property.

14Evidence gleaned from the squares along the western edge of the unit suggests that the area may have been graded down to a level just above the subsoil. There are a number of recent features which either intrude into the subsoil from the bottom-most topsoil layer or lie between the lowest topsoil layer and the subsoil. Most notable are the two shallow linear features (contexts 29BB-97 and 29BB-98) which overlie the drainage ditch. The orange-yellow clay with which they are filled is usually indicative of recent disturbance. Furthermore, asphalt shingles were found within the lower topsoil/loam levels. Thus, many Tucker-period features in this particular area may well have been graded away.

4 × 2 Meter Unit

The second area investigated was in the central portion of the garden, in the area of the colonial revival path and presumably near a central Tucker path. The purpose of this unit was to identify and locate Shurcliffs axial path as well as the earlier eighteenth-century Tucker path. The unit in this area was centered over the top of a very prominent ridge which was visible on the surface and which had been tentatively identified as the axial path for the Shurcliff garden. The original 2 × 2 meter unit was expanded to the west when it became evident that not only had a series of paths been encountered, but that the edge of a larger feature, extending westward, had also been uncovered.

The stratigraphy and soil characteristics in this area were considerably different to those identified in the 6 × 6 meter unit. Clearly, there are very different processes taking place and the land use was different. It is obvious that below the modem topsoil layer there is very little disturbance; early features lie within 10 cm of the ground surface. Not only are there a number of eighteenth-century features intact in this area, but also a number of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century layers.

A thin layer of topsoil lay immediately below the sod. Unlike in the 6 × 6 meter unit, however, there was a heavy concentration of marl within this stratum. In the central section of the unit this soil was very shallow, 8 cm or less, while on either side it was up to 20 cm in depth. The marl (29BB-63) appears to be a path composed of coarse grayish brown marl and medium to large shells (including pieces of large scallop shells) with some brick inclusions. This path was 80 cm wide and ran north-south the length of the unit. In profile, this feature had a half-moon shape with the center built up and tapering off to each side. A thin lens of red-brown clay used as a support underlay the marl. This is typical of construction of modem paths in the Historic Area (Edwards, personal communication, 1994) and serves to seal the path bed.

A series of similar paths (Figure 8) were found below context 29BB-63. Whereas the uppermost path was excavated completely, lower ones were sectioned and the southern half removed first. Later, the northern section of the paths and the surrounding topsoils were removed down to the level of the natural subsoil.

Beneath the red-brown clay, another layer of marl was encountered. Similar in many ways to that above it, context 29BB-64 was composed of a less compacted yellow-brown marl. Shell inclusions occurred but the fragments were smaller than those recovered in context 29BB-63. Some clay inclusions were noted, likely the result of mixing from

15

FIGURE 8. Path features in 4 × 2 meter excavation unit.

the lens above. Context 29BB-64 was approximately the same width and depth as the path above but did not have the same built-up appearance as the upper one.

FIGURE 8. Path features in 4 × 2 meter excavation unit.

the lens above. Context 29BB-64 was approximately the same width and depth as the path above but did not have the same built-up appearance as the upper one.

A third path feature lay underneath context 29BB-64; context 29BB-74 was the deepest of the three marl paths, up to 20 cm thick and 120 cm wide. Like the uppermost path context 29BB-74 had a distinct built-up appearance with a high center which tapered off towards the edges. The marl which made up this path was the lightest in color and the most loosely packed. Some brick fragments occurred within the context, increasing in number and size near the bottom of the layer.

The final and oldest path feature is a thin, flat line of marl and brick fragments which extends from near the east wall of 1338N/779E westward two meters. At maximum the feature (context 29BB-90) is no more than 5 cm deep. This path has been identified as a Tucker-period feature. A thin layer of brick fragments and brick dust (context 29BB-91) was found in the north section, running adjacent to the north wall. It appears that it may underlie the lowest path and may in fact be part of that feature.

The lowest cultural stratum identified in the eastern unit lay beneath the brick lens and was identified as a layer of dark silty, very soft soil. The layer was quite deep (up to 20 cm) and produced a few artifacts including pieces of lead window came. This soil in turn, overlay the lighter colored subsoil. It was initially thought that context 29BB-88 represented a localized feature, limited to the area beneath the path, but it was later found that it extended across the original 2 × 2 meter unit and appeared to extend westward under- 16 neath the debris spread described below. It was therefore hypothesized that this soil is indicative of shallow plowing or tilling of the property and would therefore relate to period pre-garden period, or even pre-Tucker occupation, when the land was being prepared for agricultural use. This layer has a TPQ of 1779.

The western half of the 4 × 2 meter unit was considerably different from the east side. It was expected that either a cross path and/or planting beds would be encountered in this area. A similar dark brown topsoil with marl inclusion was found below the sod.

Underlying this was a layer of marl mixed with topsoil (context 29BB-95) which sealed a debris spread below. The debris spread (context 29BB-100) was composed of large chunks of mortar, brick and shell sitting within marl matrix (Figure 9). There did not appear to be any regular pattern to this feature and indeed the edges of the spread have not been delineated. The debris spread was left intact, in order to preserve it pending future excavations.

The function of the debris is unknown, but it looks very much like destruction material. While it is not yet known whether it is related to a construction or renovation episode of the house itself, Dearstyne (1952) notes that in addition to the original construction following the relocation of the house there are several periods of renovation during the period from 1792-96. It is, however, equally possible that this could relate to some other structure such as an outbuilding. No artifacts were recovered from this layer, but the marl sealing it yielded a TPQ of 1805. There is some indication that this spread extended east to at least the far side of the paths. Context 29BB-89 is very similar in nature to 29BB-100, containing a slightly lower concentration of mortar and brick debris within a marl matrix. This was uncovered on the east side of the three upper paths and above the Tucker

FIGURE 9. Debris spread and central path in 4 × 2 meter excavation unit.

17

path. In addition, several large pieces of debris, brick and marl were found within the top layers of the upper pathways, suggesting that three of the paths post-dated the debris spread and that the spread itself was cut through by the construction of all of those paths except for the lowest Tucker-associated path. Both context 29BB-95 and 29BB-89 returned a TPQ of 1805. As these contexts clearly extended beyond the limits of the excavation the extent of the debris is as yet unknown.

FIGURE 9. Debris spread and central path in 4 × 2 meter excavation unit.

17

path. In addition, several large pieces of debris, brick and marl were found within the top layers of the upper pathways, suggesting that three of the paths post-dated the debris spread and that the spread itself was cut through by the construction of all of those paths except for the lowest Tucker-associated path. Both context 29BB-95 and 29BB-89 returned a TPQ of 1805. As these contexts clearly extended beyond the limits of the excavation the extent of the debris is as yet unknown.

Several round holes were found to cut into the overlying marl (29BB-95). Of the four holes, two were sectioned and excavated. They formed no discernible pattern. The first, context 29BB-101, was notable by the fact that large pieces of brick and mortar were found to ring the top. Upon excavation the hole was extended downward 36 cm and found to be empty with little or nothing in its size and shape to indicate function.

The second of these two features (context 29BB-81) was located near the south wall (see Figure 9) and was found to cut into the supposed Tucker-period path. The hole, which was slightly shallower than context 29BB-101, contained a dark brown loam with marl inclusions. Contained within this hole were two rooster skeletons. The 1928 map shows several structures located near the excavation area, one of which is labelled "hen house." Photographs taken about the same time also show a small structure in this area. Apparently, then, this hole relates to a later addition to the Tucker property and probably dates to the late nineteenth century or the early twentieth century.

As noted above excavation was halted at the level of the debris spread. However, the profile along the west wall indicates that the underlying stratigraphy is similar to that in the adjacent unit. Beneath the debris spread there appears to be a layer of dark brown loam underlain by the brown silty sand noted as context 29BB-88.

The excavations completed to date in this area suggest that there was heavy activity here throughout the Tucker and Coleman occupations. Not only is there clear, well-preserved evidence of Arthur Shurcliffs colonial revival path(s), but also of an earlier Tucker-period path. The disturbance over the 4 × 2 meter unit was minimal, so that both the early eighteenth-century features and the later nineteenth- and perhaps twentieth-century alterations were also preserved.

The three upper paths have been identified as Shurcliff or post-Shurcliff paths. There is a similarity both in composition and in size that suggests that they are related to one another. Unlike the lowest path, which is flat, these have all been built up, crowned at the center. While the upper paths are made of marl, there is some evidence (as suggested by context 29BB-91) that there was also some brick rubble in the lowest path. The dates which were yielded from the artifacts show a progression back in time from 1880 for the uppermost path, to 1857 for the second path. The topsoil overlying these upper paths appears to be the result of a single episode. Furthermore, the three paths range from a minimum width of roughly 80 cm to 120 cm, while the lowest path is in excess of two meters. Finally, both the stratigraphic position of the lowest path and the nature of the artifacts within it suggest that it is an eighteenth-century feature.

Future Recommendations

During the 1994 field season the focus of the excavations was in the large 6 × 6 meter unit. While on the one hand important information was gathered, particularly that relating to the property line, clearly this was a low activity area. Excavations located over the central path indicate that the land-use patterns in that area are very different. In the future, excavations should be concentrated to the west, nearer to the central portion of the back yard. Places which should be tested include the area north of the back door and north of the restored kitchen (Figure 10). Strategies for future excavations have been developed and are more fully described in a proposal for further landscape archaeology on the St. George Tucker lot (Garden and Meatyard 1994).

While it is clear that the excavations at the Tucker House were successful, it must be remembered that to date they have yielded only preliminary data. The information received so far does indicate that there was a central path in Tucker's garden, and several other eighteenth- and nineteenth-century landscaping features have been identified. However, it should be stressed that those features which were found are limited to pathways and boundaries. No planting beds have been found. Therefore, the layout and the style is, at present, unknown. There remains a distance of over fifteen meters between the two paths which require excavation, as well as another area over twenty meters between the property line and the central path which are crucial to the understanding of the landscape plans of Tucker.

FIGURE 10. Proposed excavation area—St. George Tucker garden.

FIGURE 10. Proposed excavation area—St. George Tucker garden.

In both of the excavation units it was clear that here is a high degree of preservation of early features. The layer of silty soil (context 29BB-88) was very promising, as it appears to indicate that there are features intact which may relate to at least to the initial Tucker occupation and could in fact prove to predate that period.

It is imperative that future work be carried out in the Tucker garden. Without additional excavations it will be impossible to discover the grammar of St. George Tucker's landscape and a valuable opportunity to gain insight into the practices and ideology of gardening in the eighteenth century will be lost.

Footnotes

References Cited

- 1993

- A Proposal for Restoring St. George Tucker's Williamsburg Garden. Unpublished manuscript on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia

- 1990

- Archaeological Investigations at Shield Tavern, Williamsburg, Virginia. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1952

- Architectural Report, St. George Tucker House. Unpublished manuscn file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1988

- A View from the Top: Archaeological Investigations of Peyton Randolph's Urban Plantation. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1994

- St. George Tucker Landscape Archaeology Proposal. Unpublished manuscript on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1989

- Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy. Second edition. Academic Press, London.

- 1992

- The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

| Context # | Feature/Layer Description | Sample Type | Taken by* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 29BB-44 | Rubble and oyster shell pathway | Pollen column | GK |

| 29BB-44 | Rubble and oyster shell pathway | Pollen samples | GK |

| 29BB-121a | Eighteenth-century loam | Pollen column | MCG/KBM |

| 29BB-121b** | Eighteenth-century loam | Pollen column | MCG/KBM |

| 29BB-133 | Drainage ditch/planting bed | Pollen column | MCG/KBM |

| 29BB-1342 | Possible planting hole | Pollen column | MCG/KBM |